The 'Permitted' Dystopia: Why the Bunnings AI Ruling Exposes Australia’s Broken Privacy Law

A recent Administrative Review Tribunal (ART) decision, which gave Australia's largest hardware retailer, Bunnings, the green light to resume using high-impact facial recognition technology (FRT) on its customers, is more than a technical legal ruling. It is a material, structural blow to the fundamental right to privacy in the digital age. The decision, which overruled the Privacy Commissioner's finding of unlawful use, essentially confirms a critical loophole: that a company's business interest in combating crime can be deemed a 'permitted general situation' that overrides the necessity of explicit customer consent for the collection of sensitive biometric data.

This outcome provides a stark illustration of how Australia’s outdated privacy laws—originating in 1988—are entirely unfit to govern a world saturated with real-time, intrusive Artificial Intelligence. Without a fundamental legislative reset, every Australian who steps into a retail store, navigates a public space, or uses a government service risks becoming an unknowing participant in a real-time, national AI experiment.

The Bunnings Loophole: Security Trumps Consent

In 2024, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) found that Bunnings had breached multiple Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) by deploying FRT in 62 stores between 2019 and 2021. The core finding was that the retailer collected customers' sensitive biometric information without consent (a breach of APP 3.3).

The Administrative Review Tribunal partially overturned this central finding in February 2026. While the tribunal agreed that Bunnings breached principles related to transparency, notification, and failing to conduct a proper risk assessment (APPs 1 and 5), it crucially found that the collection of biometric data was justified. The ART determined the use fell under an exception: a 'permitted general situation' (specifically, the necessity of combatting serious retail crime and protecting staff from violence).

This is the pivot point. The ruling tacitly validates the notion that an organisation’s assessment of its own security risks is sufficient to bypass the high bar of customer consent for sensitive biometric data. The use of FRT—an indiscriminate technology that captures the faceprint of every customer, not just suspected offenders—was deemed a proportionate response. This effectively lowers the regulatory guardrail for a host of AI applications in retail and public life.

A 40-Year-Old Law Meets 21st-Century AI

The Privacy Act 1988 was designed for a paper-based, analog world. While the Australian government has been pursuing reforms—most notably through the Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024, which introduced new OAIC enforcement powers and an eventual statutory cause of action for serious privacy invasions—the pace is glacial compared to the hyper-speed of AI adoption.

The Bunnings case showcases the fragility of the current legal framework against AI that can process and discard data in milliseconds. While the reforms mandate that businesses must eventually disclose the use of automated decision-making in their privacy policies (coming into effect in December 2026), the ART ruling demonstrated that, in practice, a broad security exception can be used right now to justify the most intrusive collection of data without prior approval.

The Real-Time Dystopian Experiment

Beyond retail, this legal climate encourages the expansion of high-impact AI into everyday life, turning Australian citizens into subjects of an ever-expanding, unchecked surveillance network.

- Governmental Overreach: During the pandemic, state governments trialled home quarantine apps that combined GPS tracking with facial recognition checks, raising alarms about mission creep and data centralisation.

- National Database Ambitions: Efforts to coordinate a national facial recognition database and identification system (the 'National Facial Biometric Matching Capability') have been ongoing, with law enforcement agencies like the Australian Federal Police (AFP) having already used controversial social media-derived databases from third-party vendors.

- Invisible Retail Surveillance: The AI shift is not limited to FRT. Retailers are increasingly implementing AI-powered video analytics, smart cameras, and algorithmic systems for fraud detection, supply chain optimisation, and personalised marketing. These systems, designed for 'operational efficiency,' collect real-time data on in-store behaviour, movements, and purchasing patterns, all feeding a massive commercial data stream.

When a major tribunal decision affirms that the most intrusive data collection can proceed merely by citing a 'permitted general situation,' it provides a dangerous green light for corporations to scale up the capture of our biometric and behavioural information, making consent an optional constraint.

The One Regulatory Hook: 'Momentary Collection'

One small but crucial win for privacy emerged from the ART decision. The Tribunal affirmed the OAIC's stance that the fleeting, millisecond-long capture of facial data by the FRT system still constitutes a formal 'collection' under the Privacy Act.

This legal interpretation is a victory because it means that real-time data processing—the engine of modern AI—cannot simply evade regulation by claiming the data was only held for a moment. This principle has profound implications for ad-tech, algorithmic verification, and any system that momentarily processes biometric or personally identifiable information. However, without a strong, consent-based rule, this legal hook alone is not enough to stop the tide of surveillance; it merely means surveillance must be documented correctly.

What Australians Can Do Next

As regulatory reform lags and legal loopholes are exploited, the onus falls on consumers, industry, and advocates to push for immediate change. We need a legislative framework with red lines, not just compliance checklists.

A Call to Action for Consumers and Industry:

| Action Area | Practical Step | Why it Matters After the Bunnings Ruling |

|---|---|---|

| Demand Clarity | Always look for and read the privacy signage and policy. If FRT is mentioned, ask a store manager in writing for details on data retention and who has access. | The ART upheld the breach on transparency and notification. Industry will improve signage only if consumers demand it. |

| Push for Policy | Support advocacy groups calling for the full implementation of the Privacy Act Review recommendations, especially the Statutory Tort for Serious Invasion of Privacy. | This gives individuals a direct legal recourse against intrusive AI practices, without having to rely solely on the OAIC. |

| Exercise APPs | Formally request a copy of your collected personal data (including biometric scans or vector sets) from retailers under the Privacy Act's access principles. | This forces companies to fully audit and disclose what data they hold on you, even if the collection was 'momentary.' |

| Scrutinise AI Use | When a retailer claims AI use is for 'security' or 'efficiency,' consider the proportionality. Does stopping shoplifting justify collecting the biometric profile of every customer? | Proportionality was the core question in the ART ruling. Community pushback can force the balance to tip back toward privacy. |

The era of a 'light touch' regulatory approach to AI is over. The Bunnings decision confirms that Australia’s current laws are a feature, not a bug, of this dystopian cycle of automation. It is time to treat biometric data as the fundamental human right it is and legislate accordingly, before the experiment is complete and the surveillance state is an irreversible reality.

See you on the other side.

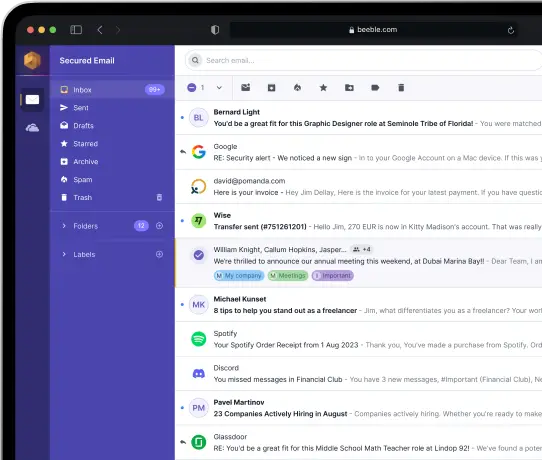

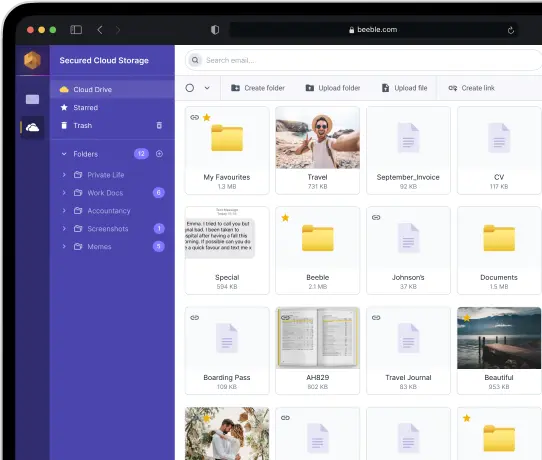

Our end-to-end encrypted email and cloud storage solution provides the most powerful means of secure data exchange, ensuring the safety and privacy of your data.

/ Create a free account