The End of the Observed Data Loophole: Understanding the CJEU’s Landmark Ruling

For years, a subtle but significant debate simmered in the backrooms of legal departments and privacy tech startups: If a company tracks your mouse movements, logs your IP address, or monitors your heart rate via a wearable, did you give them that data, or did they simply find it?

In December 2025, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) provided a definitive answer that has sent ripples through the global tech industry. The court ruled that observed personal data—information generated through a user’s interaction with a service—must be treated as data collected directly from the data subject. This decision effectively closes a long-standing loophole that some organizations used to delay or dilute their transparency obligations.

The Heart of the Matter: Article 13 vs. Article 14

To understand why this ruling matters, we have to look at the machinery of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The regulation splits transparency into two categories: Article 13 (data collected directly from the person) and Article 14 (data obtained from elsewhere, like a third-party broker).

The distinction is more than academic. Under Article 13, a company must provide privacy information at the exact moment the data is collected. Under Article 14, they often have a grace period of up to a month. By arguing that observed data—like browsing history or location pings—wasn't "provided" by the user but rather "created" by the company’s own sensors, some firms sought to bypass the immediate disclosure requirements of Article 13.

The CJEU has now dismantled this argument. The court reasoned that if the data originates from the person’s actions or characteristics, the method of capture—whether a form or a silent tracking pixel—is irrelevant. It is collected directly from them.

Why Observed Data is No Longer 'Secondary'

In the early days of the web, "collected data" usually meant what you typed into a box: your name, email, and shipping address. But in the modern economy, the most valuable data is often the stuff you don't realize you're sharing. This includes:

- Behavioral Metadata: How long you hover over an image, your scrolling speed, and your click-through patterns.

- IoT and Sensor Data: Heart rate metrics from a smartwatch or the ambient temperature from a smart thermostat.

- Technical Identifiers: MAC addresses, browser fingerprints, and precise geolocation.

By classifying this as "directly collected," the CJEU is signaling that the era of "track first, explain later" is over. If a smart car observes your driving style to calculate an insurance risk, it is collecting that data from you in real-time. Consequently, the transparency requirements must be met at that very moment.

The Ripple Effect Across EU Regulations

While the ruling is grounded in the GDPR, its shadow stretches much further. The EU's digital strategy relies on a web of interconnected laws, including the Data Act, the AI Act, and the Digital Markets Act (DMA). Many of these regulations use the concept of "data provided by the user" to define rights like data portability or access.

By broadening the definition of direct collection, the CJEU has inadvertently expanded the scope of these other laws. For instance, under the Data Act, users have the right to access data they have "contributed" to a service. If "contribution" now legally encompasses passive observation, manufacturers of connected devices will have to build much more robust data-sharing interfaces than they originally planned.

Practical Implications for Tech Teams

For CTOs and Data Protection Officers (DPOs), this ruling requires a shift in how data pipelines are audited. It is no longer enough to have a generic privacy policy buried in a footer.

Consider the "Just-in-Time" notice. If your mobile app starts tracking precise location data the moment a user opens a specific map feature, the CJEU’s logic suggests that the transparency notice must be presented right then. You cannot rely on the fact that the user agreed to a 40-page document three months ago during sign-up.

| Data Type | Old Interpretation (Common Practice) | New CJEU-Aligned Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Form Inputs | Article 13 (Immediate notice) | Article 13 (Immediate notice) |

| Cookie Tracking | Often treated as "observed" / delayed notice | Article 13 (Notice at point of drop) |

| Biometric Pings | Sometimes argued as "system-generated" | Article 13 (Notice at point of capture) |

| App Telemetry | Often relegated to Article 14 | Article 13 (Notice during app session) |

A Checklist for Compliance

If your organization processes behavioral or sensor data, here is what you should do next:

- Map Your 'Silent' Collection: Identify every point where your system observes user behavior without a direct input field. This includes telemetry, analytics, and background syncing.

- Audit Your Transparency Timing: Ensure that for every point identified above, the user has been provided with the necessary Article 13 information before or at the time the observation begins.

- Update Consent Management Platforms (CMPs): Ensure your CMPs aren't just asking for permission but are actually providing the specific disclosures required by the court's stricter interpretation of direct collection.

- Review Third-Party SDKs: Many apps use third-party tools for analytics. Since you are the controller, you are responsible for ensuring these "observations" comply with the immediate disclosure rule.

The Human Element: Restoring Trust

At its core, the CJEU’s decision is about closing the information asymmetry between giant tech platforms and individual users. When a system observes us, it often knows more about our preferences and health than we consciously realize. By forcing companies to acknowledge this observation as a direct collection of our persona, the court is pushing for a more honest digital contract.

For the tech industry, this may feel like another regulatory hurdle. However, companies that embrace this transparency—moving away from the shadows of "observed data" and into the light of clear, real-time communication—will likely find they build deeper, more resilient trust with their users in the long run.

See you on the other side.

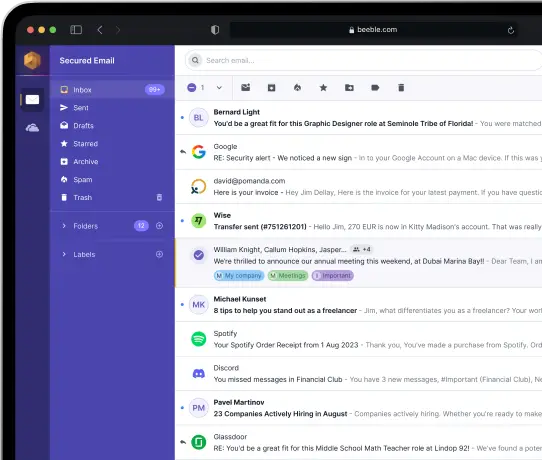

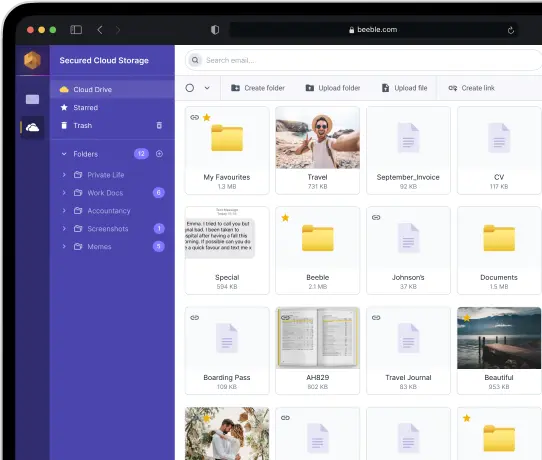

Our end-to-end encrypted email and cloud storage solution provides the most powerful means of secure data exchange, ensuring the safety and privacy of your data.

/ Create a free account